Yaba Blay’s (1)ne Drop: Shifting the Lens on Race (2014) is a beautiful, first-hand look at the true complexities surrounding the ways in which societies and peoples racialize one another and the ways in which these are institutionalized. Due to an ambiguous and vastly tangled web of psychological, historical, and countless other reasons, everyday life tends to be highly racialized.

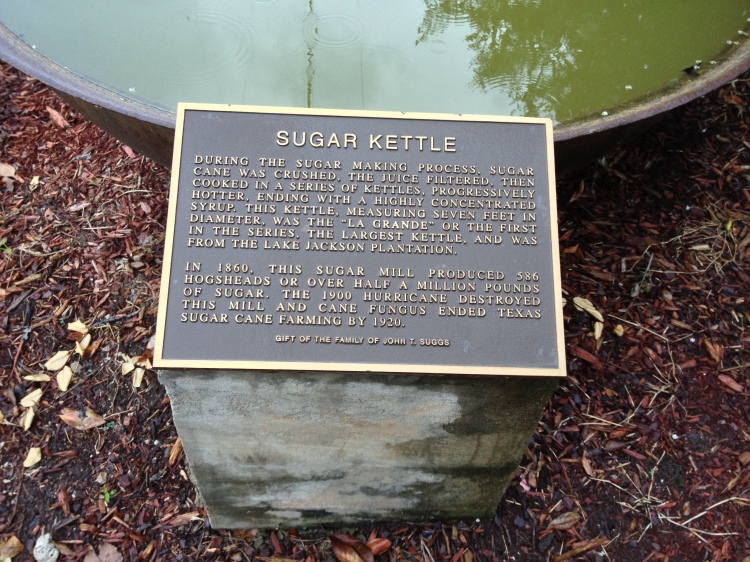

The United States was built on a foundation of “White” being good and “Black” being bad. Of “White” meaning liberty and freedom and “Black” meaning enslavement. These assumptions and corresponding racism are so interwoven into every aspect of society (similar to a cake – the sugar, for example, is everywhere in the cake but not at all directly detectable) that they go largely unnoticed and unquestioned.

Additionally, humans, without deliberate and dedicated pause, see “all Asians” or “all old people” as looking alike. This is especially true when it comes to the hue of a person’s skin. People see someone and, even if unconsciously, begin trying to figure out “who they are,” “what ‘color’ they are,” and “where they come from.” One of my favorite musical artists, Amanda Marshall, wrote a song about how glad her grandmother was when saw she saw Amanda had light skin. Listen to it here, and read the lyrics here. Most importantly, Marshall reminds us that we are all “just shades of gray.”

We know from decades of research in the liberal arts and from biology and hopefully too from basic human compassion that ultimately everyone is absolutely, positively equal and human. We know from DNA research that the vast, vast majority of all living creatures are identical. (If you haven’t read it, the American Anthropological Association’s 1998 statement titled “Race” is an excellent read. Read it here.)

Blay’s (1)ne Drop tackles these points and so much more. Blay’s book focuses on one key question: “What does it mean to be Black”?

She answers this question using 60 first hand perspectives (including her own) with over 25 countries represented in a book that is almost 300 pages. Blay interviewed each individual and asked him/her the following questions:

- How do you identify? Racially? Culturally?

- Upon meeting you for the first time, what do people usually assume about your identity?

- Do people question your Blackness?

- What is it about you that causes people to question your identity?

- Has your skin color or racial identity affected your ability to form/maintain social relationships?

- Many people assume that with light skin comes benefits. What benefits do you realize or have you experienced? Similarly, what liabilities/disadvantages have you realized or experienced?

Blay then worked with each individual to turn his/her responses to these questions and general life story into a short memoir/autobiographical sketch. Each memoir is anywhere from one to three pages, and each one is accompanied with a full page, color photograph of the individual. These photographs are particularly important because viewers see the infinite variations in people considered Black. Humans, both Black and White, for example, quite literally have every possible skin color, as well as sizes and shapes of ears, eyes, noses, mouths, etc. Blay, Noelle Théard (the main photographer), and their contributors convey this important message better than any other work I have read to date.

These essays also show a rare sense of raw honesty, so to speak. Some of the writers, for example, discuss how they used society’s stereotypes or expectations of what White or Black meant to the exclusion of others. Essays strongly convey why and how people have a fear of Blackness, as some respond to someone saying “I’m Black” with “no, you’re not Black,” and essays also show how complicated manifestations of Whiteness and White Privilege really are. Some of the accounts explain how “race” changes according to how people fixes their hair, what country they are in, or by who they are specifically around at a given moment.

I first learned about this manifestation of racialized divisions in Laura Tabili’s article “Race is a Relationship, and Not a Thing.” When talking to students, I have explained that the same person can be racialized differently depending on what they are doing and what they are wearing. For example, a woman with an “ambiguous skin hue” cleaning tables and wearing the regular uniform will be more likely to be deemed “non-White.” Take the same person and have them wear clothing considered to be more formal and telling someone else to go clean the tables and they will more likely be deemed White. (1)ne Drop has numerous real-life examples of this occurrence.

Here are two collages of photographs from the book. The colleges are from the Facebook page for this book.

The personal accounts answer much more than what it means to be Black. Indeed, the individuals in this book show how unsatisfactory the term Black really is. In the United States, all too often we consider in a highly subjective process anyone with skin of a certain hue to be an African American. This pattern of thinking is far too simple, and it is inaccurate.

Zun Lee’s vignette is a fascinating example of the complexities when it comes to anything and everything racialized. Lee was born in Germany to Korean parents. He explains how in Germany he was constantly treated as an outsider who wasn’t welcomed. As a child growing up and as a young adult he identified with and considered himself Black for social and cultural reasons, not at all because of his skin hue. He explains how that when he got to the United States people would tell him he was not allowed to check “Black” because “you’re not Black!” Lee goes on to explain how he found out in 2004 that he actually was Black. Lee’s biological father was not who he had always known but a man his mother met who was African American.

Sean Gethers, a Black albino man; Sosena Solomon, a Amhara Ethiopian woman; Angelina Griggs, a Colored woman; and Biany Pérez, a Afro-Dominican, in addition to all of the others individuals, discuss how they identify themselves and why. They show how truly complicated, numerous, and individual racialized categories are. They allow us to see how individual people identity themselves. No generalizations will be found in this book.

Collectively, these essays strongly emphasize that White and Black in no way refer to the hue of one’s skin. That being considered White and the associated Whiteness and White Privilege are constantly shifting and chaining. Above all, like much of history, the most “appropriate” and expected response to “What is your race?” or “Where are you from – no where are you really from” in some ways is don’t apply logic here.

Scholars are sometimes (inappropriately) criticized for being activist at the same time they are scholars. More and more often it is accepted and embraced they not only can we be both but that we should be both: that being passionate about what we write about makes for better scholarship. Blay’s work is also an excellent example of how one can be both a scholar and an activists at the same time and be successful at both.

In her review of Trouble in Mind, Nell Irvin Painter takes issue with how the book only focuses on individuals racialized as Black as being the victims of White individuals. Painter says this is writing about “race relations, not African-American history.” Indeed many studies looking at any social or political minority group focus exclusively on the ways in which they are marginalized by society. Blay’s approach and the results are also important, then, because she gives agency to her contributors without making them victims; she does not make them into “super humans” either.

Moreover, Blay explains that she capitalizes White and Black to serve as a constant reminder that these are socially constructed categories and identities. They essentially function as proper nouns. I also love Blay’s definition of “race” and White.” It goes:

(1)ne Drop made me think about my identity in new ways. Society would say that I am White. My immediate ancestry would say that I am White. When people hear my last name, Pegoda, I occasionally get the “where are you from, no, where are you really from” question. The name “Pegoda,” as best we know, was essentially made up when the man who first came to the United States from somewhere around present-day Eastern Europe or Russia in 1851 didn’t know how to spell his last name. Growing up as a child, I remember we would get magazines and letters in Spanish occasionally because some people deemed Pegoda to be Hispanic. I remember one day I asked my mom, “Are we Hispanic?” As an adult, I personally detest labels (yet, they are very necessary for much scholarly research), especially white/black, abled/disabled, and straight/gay – all immediately imply which one is “better” and which one is “abnormal.” My preferred identity is my name. I have a variety of names depending on the person and where I am. As a child, people called me “Andy,” starting in 8th grade people called me “Andrew,” and now, and I don’t know how or when it started exactly, at least half of the people I know call me by a new nickname, which I enjoy, “AJP.”

In summary, Yaba Blay’s (1)ne Drop: Shifting the Lens on Race promotes pride in being who you want to be. (1)ne Drop belongs on every bookshelf because in providing personal accounts it reminds us that there are countless, unique human faces that create the identities people choose to embrace and there are a whole variety of ways people embrace their identity, history, family, and associated memories. Existing mores that racialize people and the resulting assumptions are not only inadequate, they are inaccurate. Open-minded and caring readers will walk away with a new understanding of how important it is to listen and to empower others.

See also:

3. Everything is connected.

3. Everything is connected.

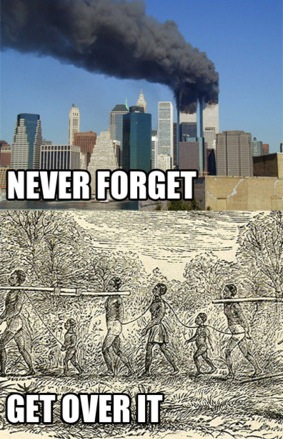

Never forget, however, is frequently a highly racialized and occasionally genderized term. It is also highly subjective. Never forget has

Never forget, however, is frequently a highly racialized and occasionally genderized term. It is also highly subjective. Never forget has