The following is a review sheet with answers exactly as sent to the parents of 5th grade students by the social studies teacher at a school near where I live. My analysis and thoughts follow the three centered diamond icons. Be sure to see the last paragraph for my full analysis.

Unit 9 Test Review

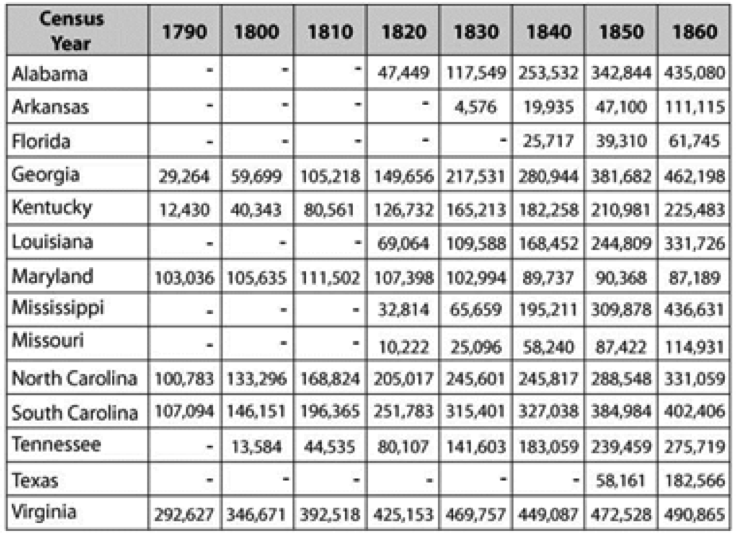

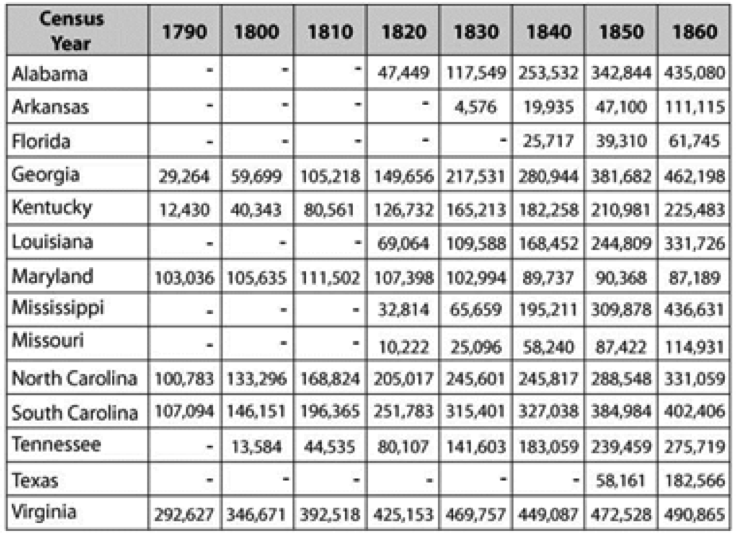

Total Population of Enslaved People,

United States, 1790-1860 (by state)

1) In 1860, which state had the highest number of slaves? Virginia

2) In 1820, how many slaves did Georgia have? 149,656

3) What do you think caused the increase in the number of slaves in the south? The increase was caused by the invention of the cotton gin, mechanical reaper, and cast steel plow. These inventions increased production on plantations.

4) List the states in order of highest to lowest number of slaves owned in 1860.Virginia, Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, Louisiana, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Texas, Missouri, Arkansas, Maryland, and Florida.

5) The Northern states economy depended on industry (factories and textile mills), while the Southern states economy depended on agriculture (famring [sic] and plantations).

6) Define sectionalism: regional loyalty.

7) The United States changedgreatly [sic] between the Industrial Revolution and the Civil War.

8) Who was the 16th President of the United States? Abraham Lincoln

He did not want slavery to spread.

He issued the Emancipation proclamation.

He believed that all people were equal and free.

9) What were 3 causes of the Civil War? Slavery, states’ rights, sectionalism (and the secession of the southern states).

10) What was one direct result of the Civil War? The end of slavery

11) REVIEW: What war was James Madison a part of? The War of 1812

12) What happened in the south as a result of the invention of the cotton gin, mechanical reaper, and the cast steel plow? An increase in slaves and food (crop) prices began to drop because there was a larger supply.

13) What is a primary source? A record of an event made by a person who saw it or took part in it.

14) What is a secondary source? A record of an event written by someone who was not there at the time.

15) Define supply: The amount of a product or service that is available.

16) When there is a shortage of supplies or goods (or a higher demand), the price goes up on these items.

17) Define demand: The need or want for a product or service by people who are willing to pay for it.

18) Harriet Tubman led people out of the South on what was called The Underground Railroad.

♦♦♦♦

There are a variety of subtle and not-so-subtle inaccuracies and agendas in this seemingly short and innocent study guide.

The table with population numbers distorts the chronological timeline of enslavement and the number of individuals enslaved. The chart does not list population numbers for Texas during decades in which the institution of slavery was indeed present. Same for other states. The chart gets around it with its title “…United States, 1790-1860.” Likewise, enslavement occurred prior to 1790. Naturally, charts can’t be all-encompassing, but such a presentation of data perpetuates the historical memory that doesn’t recognize the role of slavery prior to the nation’s founding. By not recognizing its roots, people don’t understand the full development and legacy of all the interconnected issues. Finally, and this is a more picky point, the chart should really say “Total REPORTED population.” We know that enslaved populations were not always fully reported by their enslavers.

Question #1, #2, #4, #11, #15, #17 are basically fine but are low-level questions.

#3’s answer doesn’t allow for the reality of a very pro-slavery Constitution, group of so-named Founding Fathers, and culture in general. Additionally, the cotton gin was innovated, not invented at this time.

#5 likewise undermines the role of enslavement. BOTH the North and the South had economy’s entirely dependent on the success and perpetuation of the institution of slavery. The response required for the North is more acceptable than that for the South, as it does not recognize that slavery existed in the South.

#6 by implication perpetuates the idea of a unified North and a unified South that were divided against each other.

#7 doesn’t make sense. Plus, it suggests the Industrial Revolution was an event, rather than a process.

#8 is inaccurate in saying that Lincoln supported the notion that all people were equal and free.

#9 perpetuates the inaccurate and offensive idea that the Civil War involved other issues than the institution of slavery. From experience, the “states’ rights” argument will be and is emphasized over and over. There is NO EVIDENCE anywhere that anyone during the war thought the war was about states’ rights. This was deliberately created in the decades after the Civil War to rewrite and undermine the nation’s wrong-doings-also to create a “happy,” unified narrative for the nation.

#10 is problematic because the Civil War did not end practices of slavery for those racialized as Black and did not end racism.

#12 subtly suggests that the institution of slavery was good. Additionally, its use of “increase in slaves” hits the sensitive ear wrong, “increase in the number of enslaved individuals” is much better.

#13 is okay considering the grade level.

#14 is wrong. A secondary source is not a record of events written by someone who was not there at the time. Secondary sources are based on primary sources.

#16 doesn’t make sense.

#18 by implication over perpetuates the myth of the Underground Railroad. And Tubman did NOT “led people out of the South” – she led “ENSLAVED black men and women out of the South.” The question completely omits the role of the institution of slavery.

While this presentation of history is problematic, it is a perfect example of how history as practiced by virtually everyone, everywhere, for all of time is not intended to be accurate per se (see the first link under “see also” for my blog on this point specifically). Because if it was intended to be accurate, they wouldn’t be teaching all of these things that are known to be wrong by those who can and choose to be informed about such issues. Both these questions and answers reinforce history as popularly conceived and presented at large. They both reinforce the dominant White power structure and undermine those individuals racialized as Black. They emphasize economics and capitalism. Both undermine the role of everyday people–White, Black, male, female, etc. Both undermine the horrors and agency of involved in the institution of slavery. All of this deliberate and careful omissions and inclusions by curriculum makers work toward maintaining the status quo (with an emphasis on making good capitalists) and keeping people unaware of the realities of the nation’s past as known by evidence. Additionally, this narrative suggests that the past wasn’t that bad and that the present, by implication, is free from trouble. More importantly, these issues are further evidence that we won’t and can’t take an honest, hard look at the past and the complexities of diversity and people.

See also:

Perry’s performance is ultimately racist because it is no different than when individuals racialized as Black were prohibited from being in films and White people would paint their skin black and pretend to be Black, for example. Looking at these performances today, we can clearly see how racist, discriminatory, and derogatory these really were. Perry’s performance is what we might call “Neo-Blackface.” Neo-Blackface because there is a significant chronological gap from the decades when Blackface was popular, widely used, and acceptable. But also because there is an additional very strong cultural element today, and a variety of cultures are targets of becoming costumes, so to speak. Perry is far from the only one guilty of such performances or cultural appropriation. This phenomena has become so wide-spread that this past Halloween, there were social movements starting around the Internet’s social media websites reminding people that it is offensive to “be” an Asian, Indian, or whoever for a few hours.

Perry’s performance is ultimately racist because it is no different than when individuals racialized as Black were prohibited from being in films and White people would paint their skin black and pretend to be Black, for example. Looking at these performances today, we can clearly see how racist, discriminatory, and derogatory these really were. Perry’s performance is what we might call “Neo-Blackface.” Neo-Blackface because there is a significant chronological gap from the decades when Blackface was popular, widely used, and acceptable. But also because there is an additional very strong cultural element today, and a variety of cultures are targets of becoming costumes, so to speak. Perry is far from the only one guilty of such performances or cultural appropriation. This phenomena has become so wide-spread that this past Halloween, there were social movements starting around the Internet’s social media websites reminding people that it is offensive to “be” an Asian, Indian, or whoever for a few hours.