Historians are typically adamant that present-day events cannot be used to interpret the past. I would basically consider myself a follower of this school of thought. For example, labeling science of the 18th and 19th century that said only White males were human as mere “pseudo science” delegitimizes the seriousness of these ideas to past societies.

Historians also typically oppose “upstreaming”–or studying the past beginning with the present and moving backward in time–because such approach suggests what actually happened was inevitable. This approach might reach the conclusion that because registered individuals over 18 (except convicts) can vote, Founding Fathers created a democratic society and conditions for such society to thrive. Probably not the best example, but hopefully the overall idea is illustrated.

All the time, people interpret the past and “present” based on constantly changing circumstances, hopes, and fears. In reality, all history involves some form of upstreaming.

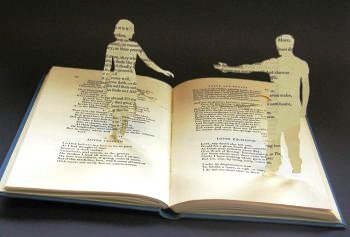

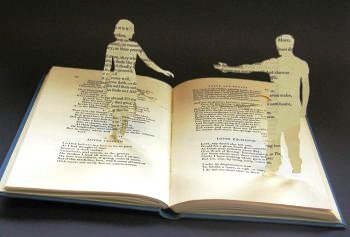

My larger thought relates to intertextuality – that is the relationship between various texts – where every thing, every one, every place is a text.

From this point of view, Barack Obama (as a text) influences Martin Luther King (as a text) far more than King influences Obama. (We could say the same about Obama’s influence on any other well-known person before now, such as Booker T. Washington or Anthony Johnson.) People en masse look at Obama’s power and achievements as a sign that racism has declined. When people learn about King, especially younger individuals, they hear his words already knowing about Obama; therefore, King’s words serve as a harbinger for a better future that happened and that was welcomed.

Or in the case of Anthony Johnson–a Black man forcefully brought to Jamestown, Virginia, shortly after its founding who bought his freedom and his wife’s freedom and owned at least one Black enslaved person–we hear the story of his life knowing about society today and use it as an example, in ways and largely unconscious way, of the forward march of “equality” in North America, without always considering related more abstract, complex issues. Obama influences Johnson far more than Johnson influences (or influenced) Obama.

To give another example, television and movies influence Shakespeare more than Shakespeare influences television and movies, in ways. People who read Shakespeare are, in general, throughly media “literate” and throughly aware of television and movies. What they hear, see, and think all goes through this filter and influences every single thing. Starting with Shakespeare and then learning about movies and television is impossible.

Since people will likely read the Harry Potter books before they will read The Tempest or Brave New World, to these readers Harry Potter will also be what influences everything else, per se.

At the same time, intertextuality asks that we recognize how consciously and unconsciously, television shows and recent literature respond to Shakespeare and even Beethoven, for instance.

Just as there have been calls for historians to stop focusing on microscopic chronologies and geographies, perhaps historians need to stop denying that articles and monographs can be free from upstreaming.

In ways, this is where notions of the activist scholar come into play. Historians (and academics in other areas) study the people and places and themes they do because of some kind of interest or desire prompted by contemporary hopes and fears. Recognizing that we are all involved in some form of upstreaming is just one more step after recognizing, which is embraced by the academy, that we are all biased.

Intertextuality gives us the opportunity to recognize how we are all connected in ways beyond the methodological, conceptual, and terminological boundaries of history or sociology or biology per se. Indeed, part of why we discuss texts in the present tense is that they are constantly alive, thriving, and changing. Susan Sontag describes this beautifully:

“I really believe in history, and that’s something people don’t believe in anymore. I know that what we do and think is a historical creation. I have very few beliefs, but this is a certainly a real belief: that most everything we think of as natural is historical and has roots…and we’re essentially still dealing with expectations and feelings that were formatted at that time, like ideas about happiness, individuality, radical social change, and pleasure. We were given a vocabulary that came into existence at a particular historical moment. So when I go to a Patti Smith Concert…I enjoy, participate, appreciate, and am tuned in better because I’ve read Nietzsche.”

See also: Uses of the Past: Legacies and Predictions and History Repeats Itself, Why I Study History, and History as a Science