While I have absolutely loved graduate school and encourage others to attend (if appropriate), there were many things no one told me about graduate school until I was there or discovered them on my own. The following are based on experience in a history doctoral program, so they may not apply in every case, especially to those disciplines outside of the liberal arts and social sciences. I would love to hear other perspectives in the comments. I anticipate that I will be writing similar blog postings on life as a graduate student.

1. You will never read a book again; yet, you will read all the time.

When you are assigned 60-100 books every semester, in addition to many writing assignments, and any other responsibilities given by the university there simply is not time to read all of everything. No one expects you to either (with very rare exceptions). In graduate school, you are learning about different arguments, perspectives, methodologies, and specialized areas.

Good skimming and strategic use of good book reviews is absolutely necessary for success. In general, I have heard and found to be true, that you should never spend more than five hours on a book. As a favorite professors says, “Historians use books; they don’t read them.” For skimming I recommend glancing over a few book reviews and the table of contents, reading the Introduction and chapter one closely, reading two or three good book reviews closely, skim the other chapters, read the conclusion, and then read over anything else necessary.

It will probably always be difficult, but this is a very effective way of learning, and it is a habit that will stay with you. You will regularly pick up a book and be done with it in a few hours or even quicker.

Your library will grow exponentially. Before graduate school, I had around 150 books. Now I have 1,600.

2. You will write all the time.

Graduate students read and write all the time. In a typical class, you will write 35-50 pages (that’s 100-150 pages a semester). One of these will usually be a long paper. The other ones are weekly précis or short essays over the reading. The two-page paper or even ten-page that took all day or even days to write and perfect as an undergrad, will be written and edited in a few hours – by necessity. You will also get very good at writing clearly quickly.

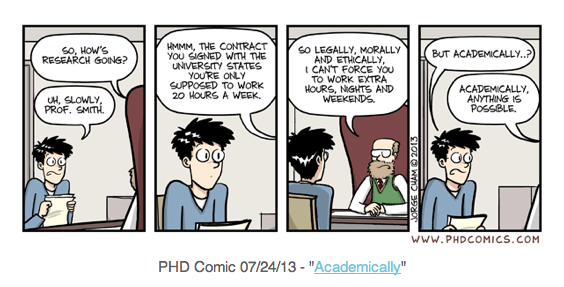

3. Being a graduate student is just half of the gig.

You will likely be working for the university you attend. This job typically provides a small stipend, some help with tuition and fees, and state health insurance. This is a good thing. Assignments vary greatly–teaching assistantships, research assistantships, etc. They usually say these jobs take 20 hours a week; however, the actual amount of time varies greatly. Some semesters my assignment has taken more like an average of 7-8 hours a week. Other semesters, the job takes 30-40 or more hours every week. This is part of the experience, part of the work load, and having too much to do. Most institutions will forbid or highly discourage outside employment in order to help you be successful.

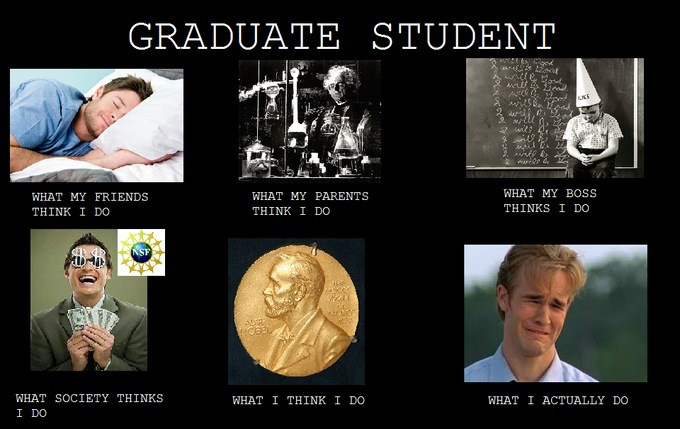

4. Graduate school is an exercise in self-torture, but you will love it.

You will always be working – both literally and figuratively. Literally in that being a historian (or whatever your area is) will take up almost all of your time. Both by necessity and because you love it. In fact, frequently, you will have more work than is humanly possible for anyone to complete. There will be weeks when you simply really do not have time to “read” a book adequately or to read every article assigned – this is normal. As an undergrad, I was always a month (or more) ahead and doing extra work; in graduate school, there simply is not enough time.

Figuratively because it changes your outlook on the world and the filter by which you see, hear, smell, and taste everything with. As a historian, I am very interested in representations, power dynamics, and how people are treated (the sociologist in me comes out regularly), and I am always, even unconsciously, analyzing things around me – you will be too.

This full immersion—like they say is the best way to learn a language—is the best way to truly become a scholar. And it is fun.

You will likely feel like you are torturing yourself at times, but you keep going at it because you love it. The hazing ritual of graduate school comes with the comprehensive examination – but I can’t tell you about that. ☺

5. Your first semester will be the hardest.

The first semester you are getting used to a completely new institution, likely a new job, maybe getting used to a new city, and getting used to many new names and faces. This in itself is a lot. You will be asked to meet completely different requirements than as an undergraduate, and you will do work that is completely different. You will have to adjust as quickly as possible. You will likely wonder, “why does the world hate me.” You will second-guess yourself – often. It is not uncommon to consider taking up your second career option early (mine was owning a restaurant!). This is all normal. Everyone went through this. Just do your best and things will be fine. If you really do find graduate school is not for you, this is fine too, but don’t change your mind too quickly.

6. You will quickly realize the consequences of the nation’s ongoing educational crises.

You will likely find that you wish you had been taught how to read, write, and conduct research much better prior to your entry to graduate school. Even more, you will likely find (especially if you are teaching in any capacity) that freshmen level students are very underprepared for college. Many of them will encounter their first essay exam ever in your class. Many will also really and truly have no idea how to study and learn in college. Learn to love teaching (as I do), and help them as best as you can. Remember college is about learning. Hold them responsible, set the standard high, but recognize that their past experiences make college psychologically, physiologically, and biologically very difficult. (Be sure to see this link on my page for articles specifically about teaching.)

7. People care about what you say. In graduate school, YOU are an expert.

You are THE specialist about your topic and areas of interests. (Although, you certainly do not have to know your dissertation topic from day one or even year one.) People care what you have to say. In classes, your participation is sincerely welcomed and required. You do not have to always be right – in fact, being wrong sometimes is good. You will always be learning more and advancing your ideas.

8. You will develop weird habits.

Graduate school will make you at least a little bit crazy, if you’re not already there. Part of this craziness happens without you realizing it. The other part is adapted as a very real and important survival mechanism. As I say: “You have to be a little bit crazy to maintain your general sanity.” One of mine is always having to have two straws in my beverages from McDonald’s and the like. You will likely sleep at weird times. You will dream about and wake up thinking about names, dates, places, citations, etc.

9. Most who start graduate school do not finish.

Graduate school is hard and different. It takes an unbelievable amount of time and energy. It requires relearning and adjustment for all students. Some people come to graduate school and discover it is not for them, some just get tired, some get good jobs, some have personal or family situations, some have interests the department cannot support, some are overwhelmed by the workload – the reasons are numerous. This all makes the completion rate lower than expected. Only three students in my cohort of ten or so are sill in the program. As long as you are doing your best and/or you are happy, there is nothing to feel bad about if you start graduate school and do not finish.

10. You will likely face rejection from family and friends.

Friends and family who have not been to graduate school do not understand what graduate school actually is or means. First Generation Graduate Students have it particularly tough. Graduate school is much more than five-to-ten more years of school. It’s a 12 hours a day, 7 days a week job and commitment. Family and friends will not always understand that even though you are at home and on your computer that you are actually working. They will not necessarily understand what it means to study all the time. They may not understand your research. You will likely encounter the occasionally comment, even sometimes from complete strangers, that you need to grow up and get a job.

11. Life starts to really happen in graduate school – if it hasn’t already.

Regardless of your age, life happens in graduate school, life really happens. As an undergraduate (3 ½ years for me), I took 15-18 hours every semester (9 in the summers), never missed a class – ever, was only sick once or twice (still didn’t miss class), and earned a 4.0.

As a graduate student, I had to miss a month of class my second semester for major surgery at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. I have been very sick several times, especially in the first semester. One of my grandmothers has been very sick for over a year, and I was a main one who could attend to her needs for a good bit of that time. I had two aunts pass away in their 50s, one of which I was very close to. Skyler, one of my four-legged family members, suddenly died my fifth semester in graduate school when he was about five. Many, many other very stressful personal and family events have happened. You will need to allow time for life. Always communicate with your professors – 99% of them will be understanding and helpful.

12. You will either have very little money or lots of debt.

You will usually receive a stipend in doctoral programs, though it is no where near enough to live on. The cost of tuition, books, gas, food, and other basic necessities (you’ll need a computer or two, too) have been increasing for a few decades. The amount the very richest are paid (rather pay themselves) is vastly disproportional to the cost of necessities and amount everyone else is paid. You will have to be very frugal in graduate school, rely on family support, and/or go into significant debt. You will need to apply for scholarships and grants when you can, but even with these you will be living at or below the poverty line.

13. Jobs are rare and endless.

Completing graduate school for individuals in the humanities and social sciences is not an automatic ticket to a tenure-track job at a university. It was not until my fourth semester in graduate school that anyone talked about this. For this past given academic year, for example, there were only four entry-level jobs at universities in the entire nation that I would have probably qualified for if I had already completed my dissertation. Maybe one or two of these were tenure-track. As a recent study said, this has always been the situation. Considering the number of people who actually graduate with their Ph.D., the job competition rate is not as bad. There are also a large group of people who desire to work outside of research universities. There are “plenty” of jobs for Ph.D.s with good experience and positive records in community colleges, other sectors of the government, private organizations, etc.

14. You will receive lots of advice but do the opposite.

This one partly derives from some quotation I read or heard, but it has a ring of truth to it. You will hear lots of people give you lots of ideas and opinions about how to best do things. Of course, listen to these and consider them. Listening to what other people say based on their experience is an excellent way toward achieving what you want. But, you also need to recognize that at the end of the day only you know what will likely actually work for you; after all, you achieved entrance into graduate school for having an already strong record. You should take risks. You should try new things. At the same time, part of graduate school – for better or worse – is figuring you own way though the program. Sometimes this is half of the battle and there frequently will not be anyone who can or will tell you what you specifically should do or need to know.

15. Graduate school will completely change everything.

As discussed in the other fourteen points, graduate school really is a life-altering experience that can never be undone. It changes how you see the world and yourself. Graduate school should make you even more open minded as you study and learn about all of the countless perspectives on the world and all the vastly diverse peoples who occupy it. To me, by going to graduate school, you are signing a life-long contract of sorts, to use your knowledge for the greater good – to in some way try and make the world a “better” place.

Here’s a really good article that address how graduate school is different from the days of being an undergraduate and how to approach graduate school as something other than being a “student” again.

Please “follow” this blog if you are a WordPress user, and/or please sign up for email updates at the top right of the homepage. Thanks for reading. Check out my other articles, too. 🙂