Teaching First Year Writing this semester continues to be an exciting, interesting journey. A few nights ago, I was trying to decide how I wanted to address a lesson introducing the broad topic of facts, opinions, arguments, and related topics. My approach always involves both discussion and the philosophy. The lesson ended up being transformative for the students, according to their oral and written responses.

Here is a brief sketch of some high points.

Ultimately, I introduced the notion that there are no facts, per se. What we call “facts” exist within a specific context, a specific language, a specific point-of-view, and a specific time and place. Simply: facts do not exist on a binary.

One of the first questions I asked was:

Fact, yes or no: There have always been females.

Fact, yes or no: There have always been children.

Fact, yes or no: There have always been gay people.

Fact, yes or no: There have always been Mexicans.

Only with the last question did students en masse begin to suspect something was up. Following this, we had a brief conversations about constructionism and essentialism, post-structuralism and semiotics, and processes of identity formation.

For example, there have not been children for most of history because the notion of there being children is a much more recent one in the grand scope of World History. Likewise, there were no “children” until the shapes c h i l d r e n were created and grouped together, assigned sounds, and then applied to the mental, subjective concept of children.

From the perspective of both biology and Queer Studies, of course, all notions of biological sexes are simply invalid.

Students love to be challenged. Students love new ways of seeing things. But, at times, this is also stressful for them.

We went through other examples. In one of the classes, someone said, “Can you name anything that is simply a fact?”

One of them said something along the lines of, “I was born March 3, 1994 – that is a fact!” Another student replied, “Well what about time zones?!” I also added comments about the social construction of time.

Another student said, “Well, science is a fact.” This resulted in a conversation about the social construction of science!

They really started to get it.

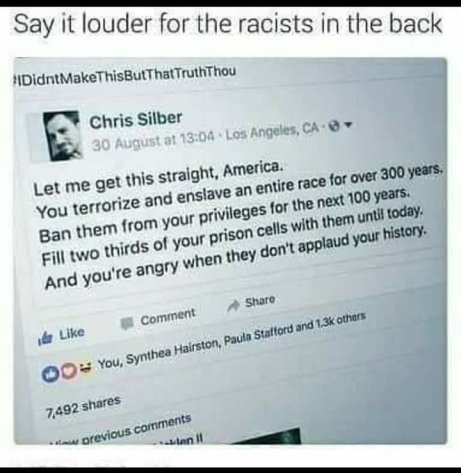

I showed the following meme and asked them, “Is this meme factual?”

“Are its absolute statements 100 percent true in all cases?” No. Then we discussed notions of historical memory and representations that are not true but accurate, per se.

Facts really are complicated. Opinions. Arguments. They are all subjective, to at least some degree whether in terms of theory, praxis, or both. Like everything else, spectrums help us to see.

We then moved to a discussion of whether or not opinions can be wrong. In both classes, all of the students said, “No. An opinion cannot be wrong.” At first, that is.

We continued to challenge that idea by discussing people who, for example, say, “It’s my opinion that the Civil War was about states’ rights!” This opinion is wrong. Factually wrong.

After this we talked about how to read texts with an eye toward the deep arguments. And how arguments, facts, and opinions are often all meshed together and are everywhere!

We looked at an advertisement for the Amazon Echo and talked about how it makes arguments for buying the product, yes, but also for a specific kind of economy and family, for example. In order to be the most productive citizens, thinkers, and learners, such seeing is powerful.

I frequently use the last 5-10 minutes of class to have students write brief responses with eyes toward what is important. On the responses after this lesson, students said they had never realized how complicated facts, opinions, and arguments could be and said they were “amazed,” “confused” (in good ways), and “in awe.”

Teaching is so much fun! Seeing students dig deep and think creates powerful bonds.

Dr. Andrew Joseph Pegoda