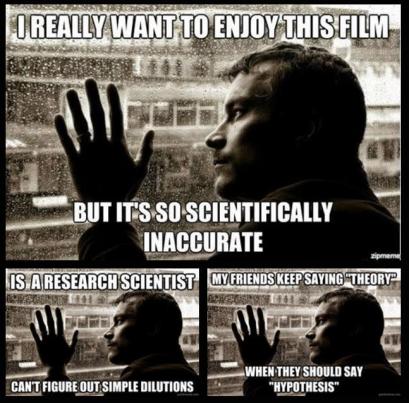

Last night I watched the 2012 Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter (hereafter, ALVH) for the second time. As a historian, I always unavoidably see movies with a somewhat different set of eyes. After all, everything has a history and involves history; therefore, movies, consciously or unconsciously, unavoidably touch on historical issues, and involve political agendas, and other concerns for the scholar. In an ideal world, movies would get history accurate, but no one really expects this. How these films present history, though, is worthy of comment. Substitute “history” for “science” in this meme, and it pretty much sums up the situation perfectly.

Of course I realize movies are basically made and watched for entertainment purposes. I actually do enjoy movies. ALVH is no exception. ALVH is full of exciting, suspenseful, and generally unique events; albeit, it has a bit too much violence and blood – but isn’t that what killing vampires is all about? On two occasions, the plot suddenly jumps froward a decade or more. There are creative cuts, too. The accompanying music is enjoyable, too (although Linkin Park is certainly far too modern for the Civil War). ALVH recasts the United States Civil War, a war lasting from 1861-1865 and basically fought between the North and South over the issue of enslavement, as a war basically between Lincoln in the North and vampires in the South.

If you haven’t seen the film or need a refresher, take a look at the trailer. There are also plenty of other good clips on YouTube.

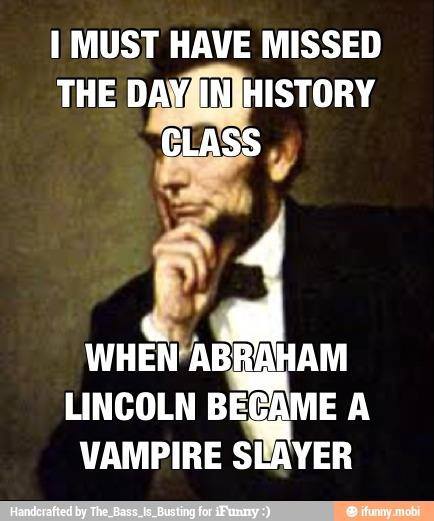

Obviously, the vampire part is fictional. Likewise, neither silver nor Lincoln’s superhero fighting skills were in any way necessary to win the Civil War. Numerous other inaccuracies also exist. Enslavement is almost never mentioned, except for a few brief and inaccurate scenes sprinkled here and there. At the beginning of the film, set in the late 1810s, Lincoln sees William H. Johnson, a black child who is not enslaved, being beaten and despite objections from his father Lincoln runs to save him; thus, Lincoln is shown from the very beginning, even as a child, to be a hero and destined for greatness. Johnson is a life-long friend and personal assistant of Lincoln’s in ALVH. In reality, the historical Johnson and Lincoln met in the early 1860s and Johnson was hired as a personal servant for Lincoln. This error gives a false impression about the possible relationship and corresponding acceptability and equality between a white and black man at this time, especially one between the President and another man who was radicalized as black. We also know from evidence that Lincoln was far from perfect in his ideas – he was a product of his time. In ALVH, it is really as if racism does not exist.

Inaccuracies also include Lincoln’s mother boldly announcing to the enslaver attacking Johnson and her son: “Until every man is free we are all slaves.” Lincoln’s mother then dies from a Vampire attack, rather than from a mysterious illness as in reality. ALVH, as does popular culture, portrays the Emancipation Proclamation as having freed enslaved peoples. (I’ll be making a post about the problematic nature of saying “Lincoln freed the slaves” in a few days.) The film mistakenly says Africans sold other Africans–while this is “correct” no shared concept of being African existed. The film also says that slavery only ever existed in the South. Errors also relate to when Lincoln met his wife, the number of children they had, etc.

More than just counting the inaccuracies, though this is indeed important and fun, as this Twitter user says, we also need to figure out what they mean.

A cultural studies/American studies analysis of ALVH, consist of countless possible readings, including the following. But, first a definition of vampire.

In ALVH, vampires serve as a metaphor for all things said to be evil and everything bad or unfortunate. Vampires receive such blame. Vampires are responsible for the death of both Lincoln’s mother and son, as well as other innocent people. Vampires are also responsible for the rise of enslavement in the South and for its distinct political identity. Although vampires could possibly represent obstacles broadly, ALVH makes it clear who vampires specifically are. Vampires are enslavers in the South in ALVH, and Lincoln fights them his entire life, in one way or another.

A few different readings come to mind:

On one hand, it could be said that vampires in ALVH demonize southerners or at the very least in an odd way hold them responsible for their actions. Southerners receive blame, though metaphorically, for their firm insistence on maintaining enslavement-although enslavement is never mentioned or dealt with in any meaningful, accurate way. For example, at one point a character in ALVH briefly mentions that the presence of enslaved people kept vampires (i.e., southerners) from being even more evil. Demonizing southerns, however, is problematic because such southerners are “othered” and made into something besides human. It also perpetuates the false notion that problems of racism were limited to the South. This does little to historicize and honor the agency of anyone.

Another take: At the end of ALVH, we hear Lincoln in voiceover saying that the enemies (i.e., vampires) fled for Europe, South America, and Asia because they knew America was forever a land of free and living men and that as a result all problems ended with the war. Thus another and equally problematic possible take on the film’s Civil War message is that since vampires were responsible for enslavement and left the nation after the war, those living here today really don’t have ancestors who were enslavers and guilty of racism and thus, aren’t in any way responsible or associated with past racism. Moreover, this would tend toward perpetuating very false arguments found across southern literature (most notably, Gone with the Wind) that say the Civil War was not about enslavement when it absolutely was. On another note, history tells us that racism was far from over after the Civil War. Many would say, it only grew worse across the nation for many decades. History also indicates over and over that the United States is in no way a land for everyone. Finally, if all vampires and thus all things evil left the nation after the war, then the film tends to demonize the rest of the world and perpetuate the equally false idea the the United States is uniquely better than all other nations in the history of the world.

And as vampires stand for all things evil, except for the one good vampire, Lincoln, the star of ALVH, stands for all things good and noble in something akin to “great men history.” Simultaneously the film has a much more negative depiction of Lincoln than typically found anywhere. From a very young age, Lincoln has an extremely strong hatred of vampires and has the goal to kill them. Indeed he does kill many. It is never really explained why the vampires are not dangerous until they are provoked. As Lincoln has this vampire-hunitng side-life, ALVH also paints him as a very mysterious man who lies all the time throughout his life in order to keep his secret. As tension rises toward the end of ALVH, Lincoln fights on the front lines and his efforts are what win the war single-handedly. Even though he receives help along the way, Lincoln receives and takes full credit in ALVH. In ALVH, this would parallel historical interpretations that say, “Lincoln freed the slaves.” The movie also oddly places full blame for the war and its progression on Lincoln. Lincoln is regularly told it is all his fault, especially, the continued vampire attacks. In this sense, ALVH takes responsibility away from southerners and ignores all of the real issues. Some interpretations elsewhere suggest Lincoln is presented as something like a “Superman” or “Spiderman” for the United States – noble, yet mysterious.

Ultimately, then, by using vampires as a substitute for Southern enslavers, and Lincoln’s absolute hate and desire to murder vampires as a substitute for all of the real political and social issues of the mid-1800s, ALVH eliminates any responsibility for enslavement from anyone and “otherizes” all of the issues and people at hand.

Regardless of other readings, the use of vampires as a substitute for slavery is very concerning and significant considering a long tradition in Southern literature that removes direct responsibility from all individuals, in the North and South, for the Civil War. Gone with the Wind (1939) being the most important and famous example.

Again, yes, the vampire part is ultra fictional, as is virtually all of the story (except the strong use of historical characters, names, places, and issues), but the writers didn’t pick the Civil War without deeper reasons and agendas. Lincoln, of course, is a natural box-office attraction, but there is more to it than that. The movie could have easily involved all fictional people and settings, especially given the on-going popularity with all things vampire, zombie related. That vampires were transposed onto the Civil War is interesting and deserves analysis, but if we can peel away the vampire story and read what the vampires stand far, important insights can be revealed. Such subtle messages are important in terms of historical memory.

Probably the most accurate and powerful parts of ALVH come at the beginning and end. They speak to interesting and important larger historical truths.

At the beginning, ALVH’s Lincoln in voiceover says:

History prefers legends to men. It prefers nobility to brutality, soaring speeches to quiet deeds. History remembers the battle, but forgets the blood. Whatever history remembers me, if it remembers anything at all, it shall only remember a fraction of the truth. For what ever else I am, a husband, a lawyer… a President… I shall always think of myself as a man who struggled against the darkness…

These are not the historical Lincoln’s actual words, but these works speak to truths. ALVH even is a perfect example of this being true.

And then ALVH concludes with this powerful and odd image and Lincoln Park song Powerless. When I see it, I think of all the actual blood, much of it from enslaved individuals kidnapped from the continent of Africa, involved in building the United States and perhaps the blood that remains on our nation’s hands, to use the cliché.

“Powerless”

You hid your skeletons when I had shown you mine

You woke the devil that I thought you’d left behind

I saw the evidence, the crimson soaking through

Ten thousand promises, ten thousand ways to lose[Chorus]

And you held it all but you were careless to let it fall

You held it all and I was by your side, powerlessI watched you fall apart and chased you to the end

I’m left with emptiness that words cannot defend

You’ll never know what I became because of you

Ten thousand promises, ten thousand ways to lose[Chorus x2]

And you held it all but you were careless to let it fall

You held it all and I was by your side, powerlessPowerless [x3]

Altogether ALVH has an usual mix of thought-provoking metaphors, accurate and inaccurate information, packaged in a seemingly harmless film. The concern from a moral, historical, and political standpoint, however, relates to the continued inability for people to face important historical events head-on. We, as a society, need to be careful to give the memory of Lincoln, the Civil War, enslaved peoples, and all the others justice.

Please “follow” this blog if you are a WordPress user, and/or please sign up for email updates at the top right of the homepage. Thanks for reading. Check out my other articles, too. 🙂